|

|

TALISMANS | READINGS | COURSES | BOOKS | CDs | SOFTWARE | POSTERS | PAYMENT | CONTACT | SEARCH |

|

| Christopher Warnock, Esq. |

from Eugenio Garin's Astrology in the Renaissance

| HOME |

|

|

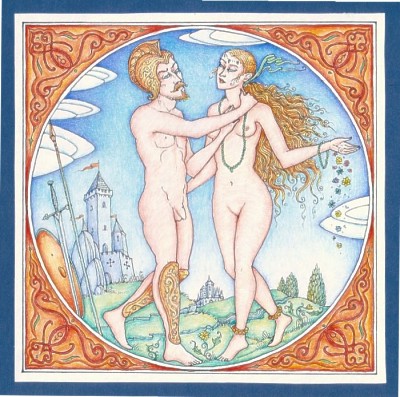

Mars & Venus |

in

Renaissance

Astrological

Magic

Introduction

Picatrix from Eugenio Garin's Astrology in the Renaissance

Astrology in the Renaissance

Pages 46-55

|

|

That is to say the Picatrix, a text well known to Pico and to Ficino, and used by them, but which was also widely read in the fifteenth century in a Latin version, derived from the Arabic through a Spanish mediation. It is not a coincidence that the Picatrix is the same book which Ibn Khaldun analyses and discusses when he wants to refute ritual magic and talismans. He does not in fact hesitate to define the Picatrix under its title'The aim of the wise man' as'the most complete and best written treatise on magic'. Nor is it unimportant that such a cultured thinker as Ibn Khaldun, who died in 1406 and who lived between North Africa and Egypt, should give, at that particular time, such prominence to a work whose influence was only just beginning to be felt in the fifteenth century in the West, whilst in the preceding period the traces of it were scarce and uncertain."

|

|

The original Arabic version, falsely attributed by the same Ibn Khaldun to Maslama al-Magriti, which is in reality a very mixed compilation, a summa, at times a kind of anthology, shows signs of being a book put together 'in the kingdom of Spain' around the middle of the eleventh century between 1047 and 1051. Hellmut Ritter, one of its first scholars, supposed that the Latin version of the Picatrix was a corruption of Hippocrates. But he later abandoned the hypothesis, which was nevertheless taken up by Corbin. It seems from the internal evidence that Biqratis (Buqratis)-Picatrix is the name of the compiler himself: Tiber, one reads in the Latin version, quern sapientissimus philosophus Picatris in nigromanticis artibus ex quampluribus libris composuit (the book on the necromantic arts which the most wise philosopher Picatrix compiled from many books). From the Latin manuscripts it turns out that King Alfonso had the work translated from Arabic into Spanish in 1256; and from this came the Latin version, which has never been published, and of which various manuscripts are known, but all written relatively late. In 1933 Ritter published a critical edition of the Arabic text which was then translated into German in 1962 in an accurate version produced by Ritter together with Martin Plessner.

|

|

Where does the exceptional importance of the Picatrix really lie? Precisely, perhaps, because it puts all the vast inheritance of ancient and medieval magic and astrology into, on the one hand, the theoretical neoplatonic picture, and on the other the hermeticist one. And this in terms which are surprisingly close to the work of the fifteenth-century Platonic movement, a closeness which is in fact so marked that it cannot be pure coincidence. In other words the interest of the Picatrix does not end with the iconological contributions already employed by the Warburg Institute: from the history of neoplatonic metaphysics to astrological discussions, from theories of the intellect to magical and alchemical questions, from 'pagan' liturgy to talismans and amulets. The end of the wise man of the pseudo-Magriti covers very wide areas of the history of culture. And they are all areas relevant to the scholar of the Renaissance. The work's point of departure is the unity of reality divided into symmetrical and corresponding degrees, planes or worlds: a reality stretched between two poles: the original One, God the source of all existence, and man, the microcosm, who, with his 'science' (scientia) brings the dispersion back to its origin, identifying and using their correspondences.

|

|

The picture of man given by the Picatrix is not without detail; a picture which is in some ways similar to the hermetic Asclepius, and in others similar to the Oratio of Pico dells Mirandola (who also had the Picatrix in his library) He is a lesser world similar to the greater world; he is a complete, animated and rational body with a rational spirit ... And rational means capable of knowledge ... He has a spherical head and the capacity to judge; he has science and writing; he discovers techniques ... he laughs and cries ... he has within him a divine power and possesses the knowledge of justice for governing cities ... he knows that which is useful and that which is harmful ... he discovers fine inventions, he performs miracles and makes marvellous images; the forms of the sciences are brought together within him, and he is separated from all other sensible animals, and God has made him the maker and inventor of all science and knowledge, able to explain all its qualities, to accept everything in the world, to understand the treasures within everything with a prophetic spirit ... Man understands all intelligent forms and everything in this world ... and they do not understand him; all creatures serve him, yet he is the servant of none; he mimics all other animals with his voice when it pleases him. With his hands he can make images which resemble them; with his words he numbers, narrates and explains their natures and actions ... With his natural voice man has the capacity to make the sounds of all other animals and he can change their form as he pleases ... The general form of man is the home of the form of the spirit in general.

|

|

The sage is he who discovers the correspondence and unity in the occult as well as the diversity: 'Ad altiora procedere, discurrendo quousque ad mathematicalem veniamus, in qua virtus completer hominis, et per scientias speculativas est perfectos. Et hoc est bonum quod quaerit homo ... Et ille qui ad ista attigerit, gaudium, laetitiam et durabilem sapientiam habebit in perpetuum et sine fine' ('to proceed to higher things, by hastening through until we come to mathematics, in which man's virtue is completed and perfected through the speculative sciences. And this is the good which man seeks ... And he who attains these will have joy, happiness and lasting wisdom for ever and without end'). Conversely, he who is not a scholar and a magus is only a man in name. ('He should not be called a man except in name, form and shape of a man.')

|

|

Inside (the city) stands a castle with four gates. On the eastern gate is placed the figure of an Eagle, on the western one that of a Bull, on the southern gate that of a Lion and on the northern one that of a Dog. He introduced the spirits which could speak into the images, and no one could enter the castle without their permission ... On the top of the castle he had built a tower which was twenty cubits high, on top of which he put a globe whose colour changed every day for seven days. And at the end of the week the first colour returned. So every day the city shone with a different colour.

|

|

When I wanted to reveal the science of the mystery ('secrets opens mundi') and of the processes of creation, I found a dark cave, full of shadows and winds. I could not discern anything because of the darkness and I could not keep my lamp alight because of the force of the winds. Then a being appeared to me in my sleep whose aspect was one of great beauty. It said to me: take a light and put it in a glass lantern which will protect it from the winds, so that it will shine despite the strength of the wind. Thus it will penetrate into the subterranean room. We are obviously dealing with a commonplace, but one's thought flies to another text, with a different power, inspiration and meaning, although similar in its images, Leonardo's cave. Here too we find the wind ('the arctic North wind strikes again in its rage'); and then the dark cave and the search for the hidden truth:" Unable to resist my eager desire and wanting to see the great multitude of the various and strange shapes made by formative nature, and having wandered some distance among gloomy rocks, I came to the entrance of a great cavern, in front of which I stood some time, astonished and unaware of such a thing. Bending my back into an arch I rested my tired hand on my knee and held my right hand over my downcast and contracted eyebrows: often bending first one way and then the other, to see whether I could discover anything inside, and this being forbidden by the deep darkness within, and after having remained there some time, two contrary emotions arose in me, fear and desire - fear of the threatening dark cavern, desire to see whether there were any marvellous thing within it.

Doubtless we are on a different track with Leonardo, far from magicians and astrologers, even if for him man is still a microcosm, and so an integral part of the whole, symmetrical and linked to the whole by infinite and mysterious bonds. None the less the culture which surrounded him, which conditioned him and against which he fought a sometimes equivocal battle, was largely dominated by the inclusion of magic and astrology in the framework of a neoplatonic metaphysics, which characterise Picatrix. At one point Leonardo, in his crude polemic against necromancy and alchemy and magic, exclaims: '0 mathematicians, shed light on this error! The spirit has no voice, because where there is a voice there is a body.' Picatrix on the other hand, and the work of Ficino, are full of voices without bodies.

|

|

The relationship between neoplatonic metaphysics and practical magic shows a precise symmetry: the magic of incantations is the 'scientific' moment suitable for platonic theology. As the former is in reality a 'poetic' vision of the cosmos, so the latter is a 'rhetorical' technique. If the whole is pervaded by'souls', those which move the planets are'spirits' ('It is possible to speak with the spirits of the planets') - as Picatrix says and as Ficino was to say. In an animated and consentient universe, connected and working together, in an all-understanding sympathy, one speaks with the stars, the plants, the stones: they pray, they command, they constrain, making more powerful spirits intervene through prayers and appropriate speeches. 'Science' comes to a magical formula, not a mathematical one; its methods and its instruments are incantations, talismans, amulets, not machines. The word, the verbum, the speech, of which Picatrix speaks so much, is the word which rises to the stars or to the stellar divinities or reaches the 'spirits' of things: quia verbum in se habet nigromantie virtutem (because the word contains in itself the power of necromancy). As the Arab text says, 'speech is the most beautiful kind of theoretical magic.'

If you wish to delve even deeper into this fascinating area I offer my Planetary Magic Mini-Course and Mansions of the Moon Mini-Course, which allow students to immediately start making talismans and elections and are a great introduction to my longer Electional Astrology Course, Horary Astrology Course and Astrological Magic Course.

HOME

Please Contact me with any Questions & Comments

Specializing in Horary Astrology, Electional Astrology Astrological Magic and Astrological Talismans.

Copyright 2006, Christopher Warnock, All Rights Reserved.